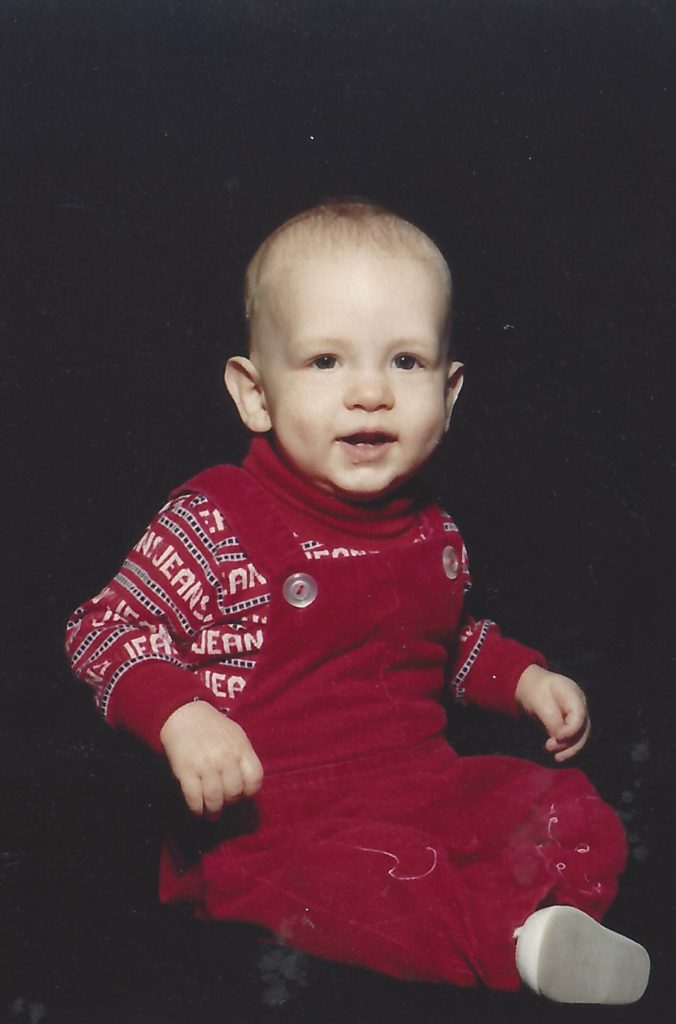

Today is my son’s fortieth birthday. Yes, 4O. Every year at the moment of his entrance into the world, I call or text him. I may sing a silly “Happy Birthday” song to him, or I may just wish him happiness on his special day. Or, as today, I might sing few bars of “Bye Bye, Blackbird” to him.

When he was still a baby, I would sing to him often when rocking with him on my lap. “A Froggy Went A-Courting” was one we enjoyed, but “Blackbird” was our favorite. My baby would gurgle and laugh as I bounced him to the rhythm.

Pack up all my care and woe

Here I go singing low

Bye, bye blackbird

Where somebody waits for me

Sugar’s sweet, so is she

Bye, bye blackbird

No one here can love or understand me

Oh what hard luck stories they all hand me

Now make my bed and light the light

I’ll arrive late tonight

Blackbird, bye, bye.

Regardless of the meaning behind the lyrics, my baby and I always shared it as a happy song, one in which the protagonist, a “black bird” was going toward better, happier times.

Each year as I celebrate my son’s birth, I return to these sweet moments in the early years when the two of us seemed, in Helen Reddy’s words, united “against the world.” Today, this celebration of his forty years is also a call out for hope, for strength to get past the many ills that plague us–terrible virus, the chaos in our government, the rise of militant groups who plot violent acts against others. So much to despair about.

But today, I choose hope that all of us may “pack up our cares and woes” and arrive in a safe place as soon as possible. It’s been a hard ride.

Fertility *

Burr Oak Street in rural Michigan

glows with brown, gold,

yellow, orange leaves.

October 9. Pains begin at 12:05 a. m.

A cool night, bracing itself

for colder nights to come.

I know the signs, count the seconds

between each throb, electric

belly currents.

I climb steps to the first floor slowly,

one at a time, brace myself,

grip iron railings,

for each wave is

like a heartbeat

like a tribal drum

like an urgent call.

Outside, wet wind blows leaves

against the house. It’s

almost Halloween.

***

At three years old I am a ghost

in white sheet, eyes peering

through ragged slits.

I moan, and my girl voice rises

through an Indiana fall night,

joins wet winds

bearing down on leaves, mostly yellow,

some orange, a damp carpet

on lawns, sidewalks.

This will be a long night of monitors

ice chips, moans, counted breaths,

dampened forehead patted dry.

At 8:11 a. m. he will emerge,

his cries like a chicken clucking.

I will take him home. By then,

trees will stand barren of leaves.

*From Portals: A Memoir in Verse, Kelsay Books 2019

I like to live always at the beginnings of life, not at their end. We all lose some of our faith under the oppression of mad leaders, insane history, pathologic cruelties of daily life. I am by nature always beginning and believing and so I find your company more fruitful than that of, say, Edmund Wilson, who asserts his opinions, beliefs, and knowledge as the ultimate verity. Older people fall into rigid patterns. Curiosity, risk, exploration are forgotten by them. You have not yet discovered that you have a lot to give, and that the more you give the more riches you will find in yourself. It amazed me that you felt that each time you write a story you gave away one of your dreams and you felt the poorer for it. But then you have not thought that this dream is planted in others, others begin to live it too, it is shared, it is the beginning of friendship and love. ”

I like to live always at the beginnings of life, not at their end. We all lose some of our faith under the oppression of mad leaders, insane history, pathologic cruelties of daily life. I am by nature always beginning and believing and so I find your company more fruitful than that of, say, Edmund Wilson, who asserts his opinions, beliefs, and knowledge as the ultimate verity. Older people fall into rigid patterns. Curiosity, risk, exploration are forgotten by them. You have not yet discovered that you have a lot to give, and that the more you give the more riches you will find in yourself. It amazed me that you felt that each time you write a story you gave away one of your dreams and you felt the poorer for it. But then you have not thought that this dream is planted in others, others begin to live it too, it is shared, it is the beginning of friendship and love. ”